The third and final season of Mob Psycho 100 picks up at a point where any other series would have ended. Protagonist Shigeo Kageyama, aka Mob, has already defeated a worldwide conspiracy of evil psychics and seemingly saved the Earth from domination. What more is there to do? For Mob Psycho 100, this is just the beginning — our hero has to decide what he wants to do with the rest of his life.

Shonen, the genre of manga and anime typically marketed to young boys, has escalation built into its formal DNA. The nature of serialized, weekly chapter releases intended to bring on regular readers, long anime seasons intended to bring on weekly viewers, and expanding merchandise opportunities intended to feed into the manga and anime means that shonen stories are incentivized to lean into regular cliffhangers. Protagonists start with a specific, seemingly impossible goal — Naruto’s quest to become the strongest ninja in his village, Luffy searching for the One Piece, and so on — and spiral outward. Each new foe is deadlier, cooler, and more interesting than the last.

Accordingly, while plenty of shonen series have deep, long-established character benches, it can also be a fundamentally individualist genre. The protagonist, whether it’s Izuku Midoriya, Naruto Uzumaki, or Son Goku, relies on others and builds relationships. Ultimately, their success and growth is expressed by individual strength, often in single combat. Your friends can give you the emotional strength to punch good, but at the end of the day, it’s your fist.

ONE, the pseudonymous mangaka behind Mob Psycho 100, flips this script on its head. His work tends to ask, “What if you already had all the power you could possibly need… and it didn’t make you happy?”

ONE’s breakout series One Punch Man is, in essence, a single joke repeated ad nauseam: Protagonist Saitama can defeat any enemy with a single punch, and, without any real challenge or adversity, struggles to find meaning in his life. One Punch Man frequently devolves into a riff on drawn-out shonen series where the protagonist’s victory is a foregone conclusion (specifically Dragon Ball), but the most compelling parts of the series pit Saitama up against an opponent he can’t beat with brute force — bureaucracy and office politics.

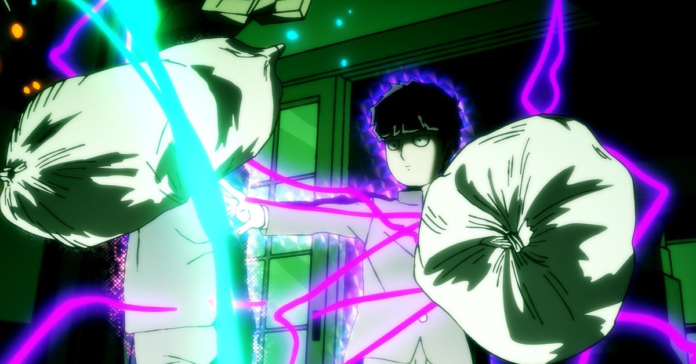

Grid View Image: ONE/Viz Media

Image: ONE/Viz Media

Though the people around him are cyborgs, psychics, and geniuses, Saitama is a completely ordinary person who simply became strong through sheer effort and force of will. (Not for nothing, the most purely sympathetic character in the series is Mumen Rider, a totally normal guy who uses his bicycle to save people.) Saitama struggles to advance in the rankings of the Hero Association as other heroes take credit for his escapades and the public frequently mocks him for his appearance. He also clashes with the other members of the Hero Association over what it means to be a hero — though the other characters all have specific, flowery ideals, Saitama just wants to be a hero for fun, something ONE underlines again and again. He isn’t detached from reality, but his invincibility leaves him perpetually aloof, bored, and put-upon.

Mob Psycho takes the basic idea of a protagonist who is definitionally all-powerful and gives it more emotional heft and seriousness, leaning into the idea that there are some problems you can’t solve by punching them. Our hero, 14-year-old Shigeo Kageyama, is probably the most powerful psychic on the planet. But Shigeo (nicknamed “Mob” because he seamlessly blends into the background) avoids using his powers as much as possible. Instead, Mob wants to be popular, and to win the heart of his childhood crush, Tsubomi-chan. It’s not just that he wants other things besides being a powerful psychic; his powers aren’t even interesting to him.

This central irony is heavily underlined early in the series, when Mob is set up to join his school’s flailing Telepathy Club, which ostensibly exists to investigate the potential existence of aliens and psychic powers. Joining the Telepathy Club would fit the logic of a more traditional shonen narrative, and give Mob a place to explore his gifts. Instead, Mob decides to join the Body Improvement Club, a group initially introduced as intimidating jocks threatening to take over the Telepathy club room. The Body Improvement Club members quickly become some of the most endearing characters in the series, relentlessly supporting Mob as he gasps and wheezes his way through stamina training and weight lifting.

Instead of using his powers to benefit himself, Mob works part-time at Spirits and Such, a psychic agency run by con man Reigen Arataka. (If you haven’t seen the show before, there are two important things to know about Reigen: He’s basically a slightly more lighthearted anime version of Better Call Saul’s Jimmy McGill, and he’s an internet sex symbol.) Mob performs exorcisms for Reigen, who claims to be a powerful psychic but has no spiritual powers to speak of.

Reigen is a casual liar who exploits Mob for his own ends, but he’s also frequently the moral center of the series — he teaches Mob the importance of not using psychic powers against people, and is fond of noting that people have all sorts of gifts, whether it’s academic talent, physical prowess, a way with words, or, yes, psychic power. Via Reigen, Mob Psycho 100 is a series that dares to watch Syndrome from The Incredibles sneer that “when everyone’s super, no one will be” and respond, “Yeah, dude, that sounds cool as hell.” (The opening lyrics of the series’ first intro song are “If everyone is not special, maybe you can be what you want to be.”) Where other anime characters’ lives are frequently defined by their gifts — Goku by his Saiyan fighting strength, Naruto by his ninja talents, and so on — Reigen exists to remind Mob that he doesn’t need to pursue something just because he’s good at it, and he doesn’t need to think of himself as being better than anyone else. Mob’s life is his own. (Except for the time he’s at work — then his life is Reigen’s.) There’s some extratextual irony in the fact that Kyle McCarley, who played the heavily exploited Mob in the English dub in seasons 1 and 2, was replaced in season 3 because he attempted to negotiate a union contract on behalf of his fellow actors.)

While Mob may receive this lesson in almost every episode, ONE’s work is in fact populated by villains who have to think of themselves as special — people who want to be anime protagonists. More or less every antagonist in Mob Psycho 100 has a debilitating case of Main Character Syndrome: They’re people born with psychic powers who think that having that gift doesn’t just mean they’re special, it also means they’re more important than everyone else around them. This is a fundamentally childish belief that defines a slew of manga and anime characters, both villains and heroes, as well as plenty of people in the real world. Mob Psycho 100 is just surprisingly deft at, essentially, telling its villains (and, perhaps, some of its readers and viewers) that they’re overgrown babies who need to go touch grass. Each time he confronts an opponent, Mob is able to apply his own experience to connect with them, because he knows what it’s like to feel disconnected from everything and everyone except your own mind. “Enemies becoming friends” is a classic anime trope, but in the case of Mob Psycho the trope has a specific thematic purpose: scratch a megalomaniacal, power-tripping boss, reveal an alienated loner struggling with isolation.

For Mob, the typical anime activity of defeating enemies becomes a way of building a community. Some of his former foes become rivals. Others use Mob as an inspiration as they struggle to build a normal life and relationships. One finds his place by working for Reigen at Spirits and Such, giving Mob the opportunity to leave the agency without worrying about leaving his mentor at the mercy of evil spirits. The third-season premiere of Mob Psycho 100 is devoted to exploring this dynamic. We the viewers might want to see Mob and Reigen ride off into the sunset as colleagues and friends who continue to work together after the end of the series, acting out the same dynamic we’ve come to know and love. But there’s no world where Mob has a satisfying adult life working for Reigen. Now, he has the freedom to truly decide what he wants to do with his life.

Of course, subverting and reflecting on straightforward power fantasies isn’t exactly new: Being ambivalent about power has been a central theme of anime since, at the absolute latest, the sixth episode of the original 1979 Mobile Suit Gundam, where protagonist Amuro Ray attempts to run away from being an ace (read: mass-murdering) pilot.

Related Mob Psycho 100 season 2 doubles down on the empathy that makes the show great

In particular, Yoshihiro Togashi, the enormously successful mangaka best known for creating Yu Yu Hakusho and Hunter x Hunter, continually engages with the limits of individual power, and the way that pursuing “power” can bump against the more important calling of being a cool and nice guy with friends and loved ones. At various points during his series, characters like Yusuke Urameshi — singularly gifted, enormously powerful heroes — decide to leave the fight in order to focus on something even scarier than demons: having a life.

I don’t have direct evidence to prove this, but it feels pretty clear to me that Togashi is a major influence on ONE. There are plenty of characters in Mob Psycho who pay visual homage to Togashi’s characters, some with similar abilities. The image of Mob, a slack-faced boy confronting incomprehensible, supernatural evil, evokes the backstory of Yu Yu Hakusho antagonist Shinobu Sensui, a prodigiously gifted child psychic who had the misfortune of becoming deputized as a cop instead of meeting Reigen. Both Mob and Reigen are put through the wringer, realizing slowly that supernatural creatures and spirits aren’t inherently evil just because they’re not human.

The murky water between right and wrong eventually breaks Sensui when he sees a cabal of rich, powerful humans torturing demons for sport, and he embarks on the path to villainy after being functionally abandoned by the callous, uncaring Spirit World. After defeating Sensui, Yu Yu Hakusho’s protagonist Yusuke Urameshi rejects Spirit World himself, and starts asking some of the same questions that plague Mob: What does it mean to hold on to your own sense of justice? Why even fight in the first place? And what would it mean to put your gifts aside for the moment and lead a normal life?

Togashi’s work explores the failings of supposedly benevolent institutions, the moral ambiguity of heroism, and the relationship between power, craft, and meaning, setting a template for how ONE engages with the same topics. But in Yu Yu Hakusho (and Togashi’s ongoing series Hunter x Hunter), these questions emerge from the structure of a more traditional shonen series, with protagonists who start with a goal but start to question themselves after achieving it. ONE’s work is able to simultaneously ignore that structure and take it for granted, putting those questions front and center from the very beginning of the story. Yusuke has to go through brutal training, countless battles, and escalating power levels before he realizes that there might be more to life. ONE’s protagonists are able to start from that position, and subsequently spend the bulk of their time trying to come to their own answers.

Mob Psycho transforms these tensions into a literal psychic toll: The series uses a percentage tracker to show how close Mob is to losing control of his repressed emotions, stemming from a childhood incident when he accidentally hurt his brother. Once he hits 100%, he “explodes” into a display of raw, destructive power. Without spoiling anything for people who haven’t read the manga, this repression is itself the final boss of the series, as Mob is finally forced to confront the nature of his own power, how he uses it, and his own discomfort with having the ability to change the world.

It makes sense that Mob himself is the ultimate obstacle he has to confront, because by the beginning of the final season, Mob really has gotten stronger. He might not be a champion athlete, but his stamina is noticeably improving. He has lots of friends, including members of the Body Improvement Club, former enemy psychics, and even the Telepathy Club. And, in shocking contrast to the wallflower we met at the beginning of the series, he’s able to form his own opinions, voice them to others, and solve problems collectively. (The second episode of the season finds Mob trying to take on a challenge scarier than any psychic: a group project for the school cultural fair.) He still doesn’t quite know what he wants to do with his life, but he knows he wants to figure it out for himself. Shonen protagonists often build community over the course of their journey, but those communities tend to be centered around their gifts, especially in school-focused settings like My Hero Academia, Food Wars, and even Naruto. But again, ONE’s work feels distinct; though Mob’s psychic powers are ostensibly the reason for the show, they’re almost completely incidental to his actual growth.

Mob is committed to doing the hard work of improving, even starting from a pitiful beginning — not just because he wants the end goal of being popular, but because the work is rewarding in itself. This quality is formally mirrored in Mob Psycho 100 itself: By conventional standards, ONE’s art looks coarse and childish, especially in the original webcomic version of both Mob and One Punch Man. But after several years (and, admittedly, with help from assistants), ONE’s art has become expressive and specific, capturing the contrast between the goofy indignities of everyday life and the cosmic-level stakes of psychic war.

The anime series is successful in large part because animation studio Bones has latched onto those seemingly sloppier elements of ONE’s work. In Bones’ hands, simple character designs and off-putting expressions become visually stunning Silly Putty. Throughout the series’ big, pyrotechnic fight scenes, Mob is often rendered as a relatively static, unmoving blob, and his lack of response or interest in the fight heightens the absurdity of the proceedings without deflating any of the spectacle. As much as he might want to be somewhere, anywhere else, he can’t quite escape being in the middle of a battle.

In these sequences, Mob remains isolated and alone in the face of whatever enemy he’s fighting. And while Mob Psycho 100 effectively makes the case for choosing to spend one’s life in community with others, it does still ultimately posit that that choice is up to the individual. Mob might not suffer from Main Character Syndrome, but he is still, in fact, the main character. ONE’s work is so good at exploring this thematic material that it raises more questions. Like, what would happen if a story simply started with the assumption that individual power isn’t the be-all and end-all, and that we have to struggle communally? Where would we go from there?

Ironically, fans looking for answers to these questions might only need to look behind the scenes. Mob Psycho convincingly argues that everyone should have the sense of freedom Mob struggles to obtain, and the ability to build the life they want for themselves. It’s a different vantage point than many of his fellow shonen protagonists have, and one that sets up potential new and compelling directions for the genre alongside other compelling, subversive series, like Jujutsu Kaisen. Mob Psycho 100 season 3 starts after most other series would end, but there’s still plenty of room for ONE to keep doing something new. Rather than having to decide what to do with the rest of his life, maybe someday we’ll see Mob actually put in the work of living.