Welcome to NHL99, The Athletic’s countdown of the best 100 players in modern NHL history. We’re ranking 100 players but calling it 99 because we all know who’s No. 1 — it’s the 99 spots behind No. 99 we have to figure out. Every Monday through Saturday until February we’ll unveil new members of the list.

“Why do you call the guy in the middle the bumper?” Adam Oates asks pointedly.

Advertisement

I think long and hard but can’t recall where I first heard the term, which refers to the forward in the middle of a 1-3-1 power play formation — a signature of Oates from his coaching career, which has been ubiquitous in the NHL over the past decade. So I just respond with a question: “I don’t remember where I first heard it. What do you call it?”

“I call him the cheese, or the diamond guy,” Oates responds.

“Is that a sandwich reference?” I ask, thinking the cheese goes in the middle of a sandwich in the same the way that a bumper occupies the middle of the 1-3-1.

“No, it’s a reference to a mouse trap. Or I call him the diamond guy because he lives within the diamond. The word bumper has never come out of my mouth. Not once. Because he’s not a bumper, he’s a weapon. He’s a threat. Bumper means facilitator. Where did the word bumper come in?” Oates asks.

“I’m really not sure,” I say. “I just assumed everyone called it that.”

“Well, I don’t, so who does?”

Oates discusses tactics for generating offense on the power play with the confidence of someone who knows to make their second mark in the side quadrant when playing first in tic-tac-toe.

One of the greatest NHL playmakers of all time, Oates seemed to approach the sport in his playing days — and in his retirement, both as an assistant coach and as a consultant working with some of the NHL’s foremost star players — as if it were a solved game. On the ice, he performed as if he were the one with the instruction manual, and as a coach, he proved it. His system for manufacturing goals five-on-four, a system that he fittingly describes with terminology distinct to that more commonly used around the league, has become a template that every single NHL team attempts to imitate.

An undrafted player out of college, where he won the national championship with Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI), Oates went on to play more than 1,300 NHL games and compile over 1,000 assists for seven different teams as one of the league’s signature pass-first centers for nearly two decades. He saw every angle, partnered with star players like Brett Hull, Cam Neely and Peter Bondra to form some of the most lethal combinations in the league in the 1990s, and after he hung up his skates went on to revolutionize how NHL power plays attack their opposition.

Advertisement

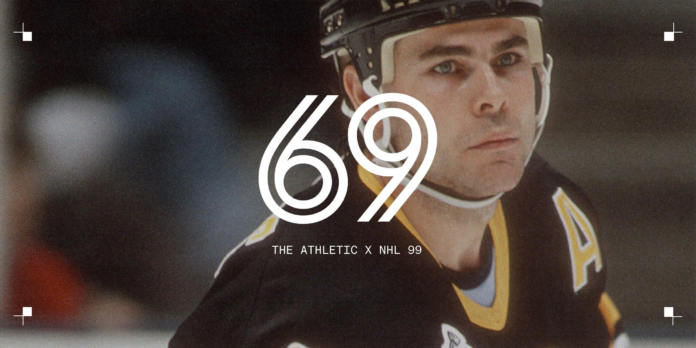

For all of these reasons, Oates checks in at No. 69 on The Athletic’s list of the greatest players in the NHL’s post-expansion era.

“There were very few people that could play the game and see the game the way he did,” recalls Hull, Oates’ longtime triggerman with the St. Louis Blues. “You can pick a handful of guys that could do the things he did. He’s the greatest passer ever, probably.

“I mean, it was crazy. It was always perfectly flat. It was right in your wheelhouse. It was always perfectly on time. He was that guy like Gretzky, little area passes, like a quarterback. Like the puck would already be coming and you weren’t even there yet, and it would be perfect. I’m not sure anyone was as good at that as Wayne was, but I’ll tell you what, Adam was the king of that.”

Bondra was also on the receiving end of some of Oates’ finest setups.

“I remember I wasn’t even ready, when we first started playing together, to be ready,” he says. “But you learn quickly to make sure to be ready always because the pass would always come. It would come from different places, between a player’s leg, or off of plays that were not plays that a regular NHL player could make.

“He’d find ways to dish the puck and my job was just to be ready, and sometimes I’d find myself shaking my head. ‘How is it possible this would happen?’ Sometimes I’d look up and feel like there was no goalie in the net because he’d have taken them off to the side with whatever he was doing.”

Later, as a coach, Oates applied his understanding of the sport to solving the problem of scoring goals on the power play.

Variations of Oates’ signature 1-3-1 power play — installed first with the Tampa Bay Lightning in Steven Stamkos’ first 50-goal season, then with the New Jersey Devils during the productive second act of Ilya Kovalchuk’s career, and most influentially with the Washington Capitals as Alex Ovechkin found an unparalleled late-career goal-scoring groove — are now ubiquitous around the NHL.

(Mitchell Layton / Getty Images)

All 32 teams utilize some variation of Oates’ 1-3-1, which includes only one defenseman, two flankers, a “bumper” in the high slot and an additional player at the net front — who isn’t often utilized as a traditional net-front guy. It is, exclusively, the only power-play formation that any team uses regularly in the NHL today.

Advertisement

There are some differences from team to team based on personnel, but over the past decade, the task for contemporary penalty-killers has fundamentally shifted. Fifteen years ago, penalty-killers would watch tape to figure out: “What is this team going to try to do?”

Now that isn’t even a question. There’s zero suspense. Contemporary NHL penalty-killers know they’re going to see the 1-3-1. The question now has shifted to “Who does this team have doing the things that we see from every team, every night?”

Absolute tactical uniformity in how teams approach manufacturing offense in five-on-four situations may be the single largest tactical shift in the NHL over the past decade — and that can be tied directly to the success that Oates had in Tampa, New Jersey and especially Washington.

“I think, every once in a while, I see something where teams are trying to do something different but they tend to quickly figure out that it doesn’t work,” Oates says. “Teams experiment and then they come back to it.

“You watch hockey every night and Ovechkin is still standing in the same spot. So who stops him? Nobody. So, that’s it. It’s just one of those things now.”

It is perhaps one of the most striking examples of how the lived experience of one uniquely clever player — and Oates happens to be the only player since expansion to go from being undrafted to racking up 1,000 career assists — became manifest tactically in their later approach as an NHL bench boss.

And in a copycat league, Oates’ approach, while hardly novel — the 1-3-1 has been around for a generation with Oates even running the system in college in the 1980s — spread rapidly to every other team.

All of this begs the question: What is it about Oates’ vision as a player that translated into revolutionizing how NHL power plays operate 10 years after his retirement?

“Hockey is a very hard game. There’s contact, there’s great athletes and it’s fast and it’s played in a confined piece. So it’s like a puzzle,” Oates says.

“I don’t do actual puzzles, but I watch a lot of hockey so I get 10 puzzles a night. Look how the whole world is into that Wordle right now. Everybody loves it…

“Well, every morning my Wordle is hockey. It is, it really is. I watch every goal — what was the good, what was the bad. I try to figure out the puzzle on every single goal.”

This in itself is consistent with how Oates played the game, according to those who played it with him.

“Adam saw the game as a puzzle, almost like a chess game, where he would think, ‘What am I going to do to beat that guy’s next move?’” says Hull. “I think that’s all personal on how you look at the game, and see the game, and figure out the game. He looked at it as a puzzle and I looked at it as how to make (defensemen) feel uncomfortable.”

“I remember what Adam taught me because I was the first guy in on the forecheck, to always move my feet on the forecheck,” Bondra recalls. “He said if you stop moving your feet, you stop putting pressure on the defender, and if they feel pressure, they might run out of time and make a mistake. So he would want me to hunt the puck because the turnovers would happen closer to the blue line where Adam was. He told me if I keep moving my feet even if I can’t get the puck, he’d get the puck back to me.”

(Bruce Bennett / Getty Images)

It wasn’t all analytical for Oates, of course. He abhorred the rah-rah phoniness of hockey’s particular brand of performative leadership. Still, he absolutely lived — and still does — for that moment in which the goal scorer, whether it was Hull, Bondra, Neely or Petr Klima, would turn to him after scoring and give him the point.

“One of the best things you see in a game is when a guy scores a goal, and I like to watch the celebration,” Oates says. “And when you see the scorer turn automatically to the guy that passed him the puck to say, ‘Nice play, man,’ I love that. It’s because players know. You know when it’s a great shot, a great pass or a great save by the goalie.

“Recognition is what every guy seeks, right? When you watch a team like Tampa Bay right now, they get the puck and what are they doing? They’re looking for Nikita Kucherov. To me, that’s the ultimate compliment. Because the players know. At the end of the day, when you have that kind of reputation, you know you’ve earned it. When a guy looks at you and gives you that nod, that’s the ultimate.”

Oates hasn’t coached in the NHL for the better part of a decade now, but there are still lots of goal scorers every night around the league who are scoring from predictable spots on the power play that they occupy, in part, because of Oates’ impact on the game.

He might not be getting the point directly from those goal scorers anymore, but it’s hard to imagine that any other passer’s ability to read the game and set up goals has lingered for this long, as a legacy on goal scoring in the game itself.

“I’m an analytical guy. I like math, I like geometry, I’m into that,” Oates says. “And when you’re a guy that played — and it can be hard to explain to people sometimes — but when you’re talking about NHL-caliber players now, do you know how good they are?

“You give these guys a piece of information and they can run with it because they’re that good And I got to watch guys like Wayne and Mark Messier and Mats Sundin and Mario Lemieux and Steve Yzerman. I mean, come on!

“These guys were incredible every night. So if you pay attention to stuff, you’re going to try and figure things out.”

It’s the figuring things out that makes Oates so remarkable. All of the other NHL players who hit 1,000 assists were early draft picks, the sorts of high-pedigree hockey geniuses who were famous at 15 and selected in the top half of the first round of the draft.

Oates is different. He didn’t break into the league until his mid-20s, went undrafted, was even the less-heralded college free agent the year he was recruited by the Detroit Red Wings out of RPI. Then he solved one of the fastest, most dynamic games on the planet and built himself into one of the best pure passers the sport has ever seen.

The same qualities that allowed Oates to quite literally build a better mouse trap as a player also permitted him to change the way the sport is played as a coach.

“One thing I know personally is how hard I have to pass the puck to beat the goalie,” he says. “I know the speed of my pass matters to the guy shooting it. There’s innate skills that guys of this caliber have developed, that’s why they’ve been able to keep rising through the ranks. And there’s subtleties well beyond skating speed and shooting skill and size and getting strong. That matters, yes, but there’s other stuff that creeps into your brain.

“So you talk about chemistry, you talk about timing, and then you talk about how if you’re behind the net and you want to pass the puck to a guy for a shot, there’s a certain speed that if you can pass it, you’re going to set up a goal, because the speed of your pass is what’s beating the goalie.

“That’s why I love the one-timer on the power play. Because if you can pass the puck fast enough, the goalie cannot react fast enough. When you go downhill on the flank, he’s already facing you. That’s a very important part of math, those extra seconds. And it’s deep stuff.”

(Top photo: Focus on Sport / Getty Images)